We're freed up to teach critical thinking

"Each year is collecting data from around 1,500 participants. And we're freed up to spend more time on data analysis"

Dr Daniel Richardson

Senior Lecturer, UCL

Transform Your Behavioural Research with AI

See how Gorilla's new tools let you build interactive AI chats, add prompts & safeguards, and automate text scoring.

"Each year is collecting data from around 1,500 participants. And we're freed up to spend more time on data analysis"

Dr Daniel Richardson

Senior Lecturer, UCL

"The experiment was picked up by BBC Radio 4 and spread through social media - at one point we had 17,000 participants"

Dr Kirsty Graham

Research Associate, St Andrews

"Instead of spending 30-40 hours sitting in a cubicle testing participants, students can recruit subjects rapidly via social media"

Prof Fred Dick

Professor of Auditory Cognitive Neuroscience, UCL

Create surveys and tasks to measure how people think and behave

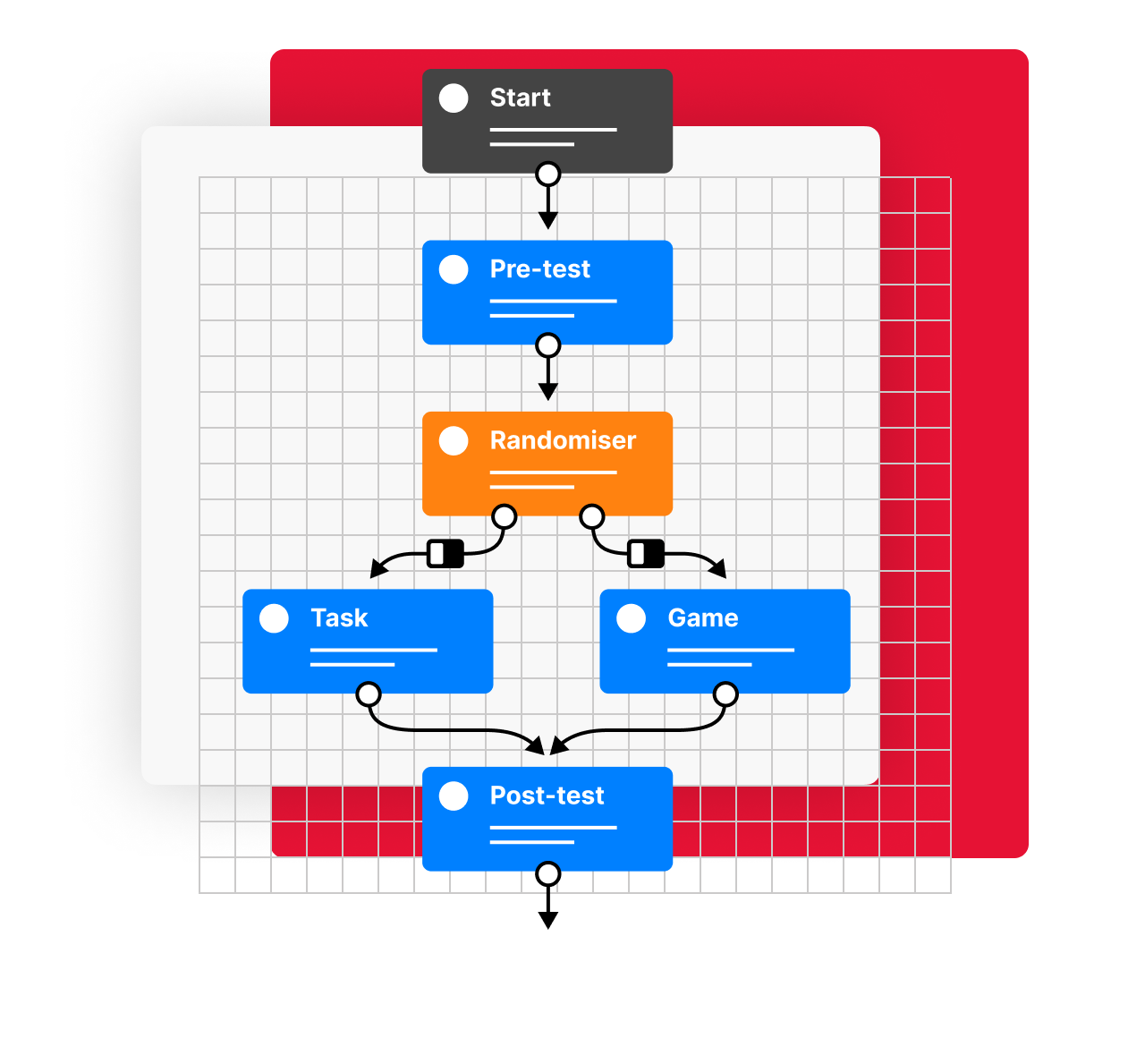

Drag your tasks and surveys into your experiment design

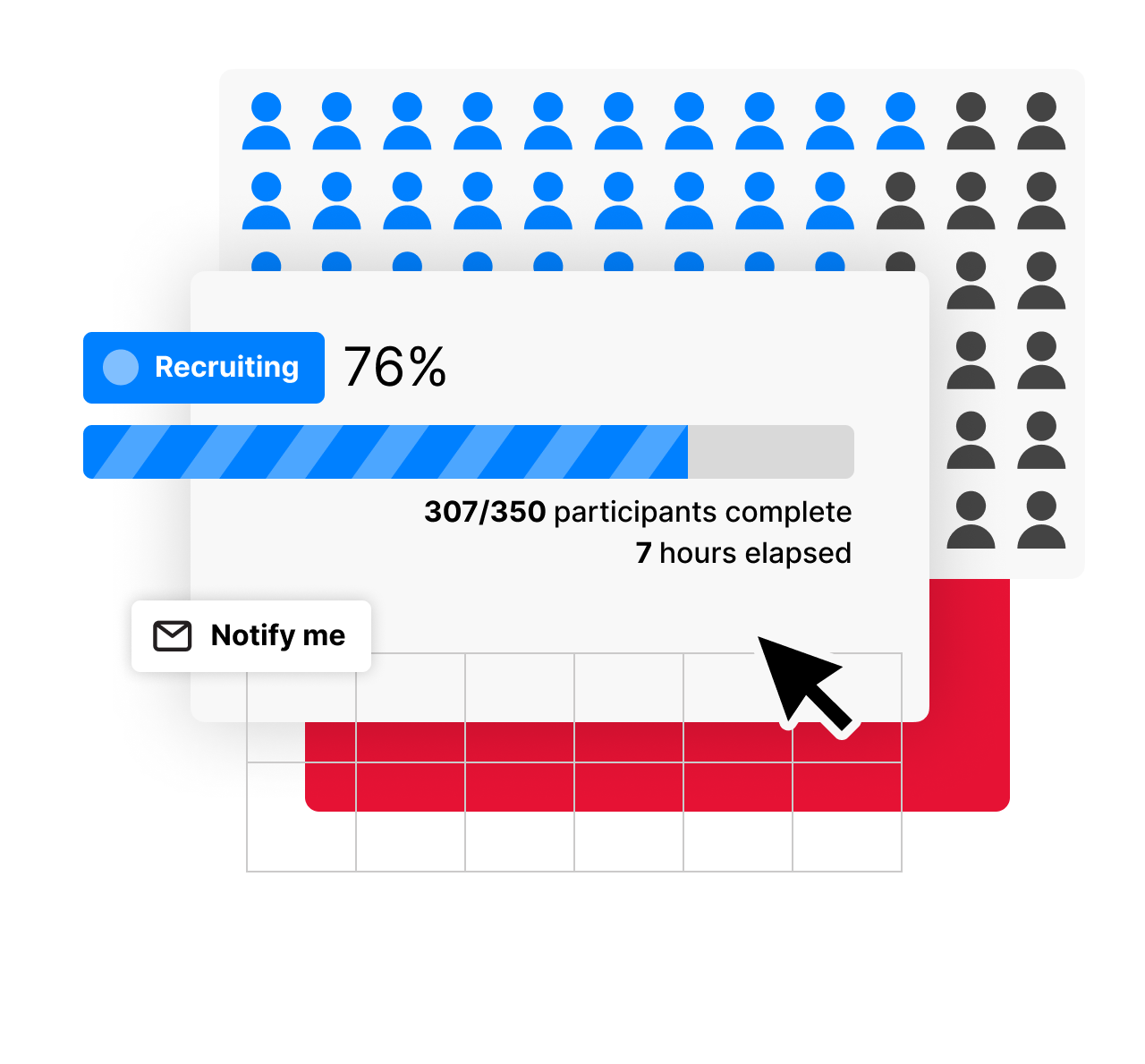

Collect validated data from participants anywhere

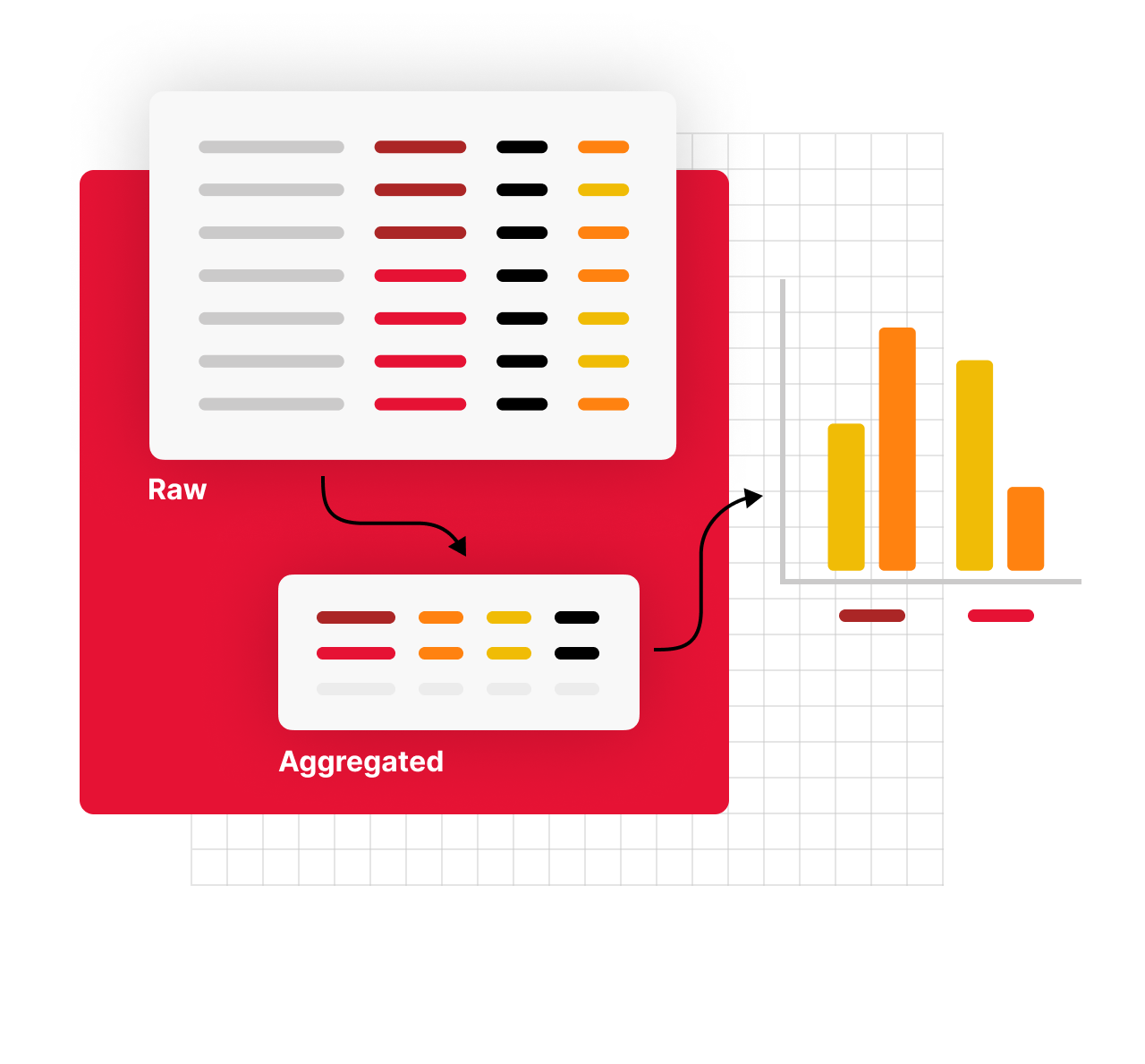

Download your data in the format you need

Intuitive Interface

Visual Design

Participant Recruitment

Data Output

"I love Gorilla as experiment builder software so much that we're transitioning our in-lab studies to this too (leaving behind E-Prime, SuperLab and PsychoPy)"

Associate Professor, University of Connecticut

Open Science

Clone ready-made samples to get started in seconds

The classic Flanker Task (or Erikson Flanker Task) is a response inhibition test used to assess participants' ability to suppress responses

Preview

The classic Stroop task - colour names match and mismatch text colour. Desktop version uses keyboard input, mobile version uses touch buttons

Preview

Participants hear a series of audio clips. You can increase difficulty using more complex audio clips, distortion or longer sentence recall

Preview

Participants are shown increasingly lengthy sequences of numbers and are asked to recall these by typing them into a text box

Preview

Participants are shown a series of faces, some with features or the whole face inverted. Participants have to detect if the face is natural or not

Preview

Easy for humans, hard for bots. One of many tasks you can add to your experiment to ensure data quality. Can you find the Y among the Xs?

Preview

"Gorilla has been my second home for three years, saving me time, effort, and money. I trust it for its high-quality data, excellent support, and intuitive interface. Our student projects have flourished, nurturing a new generation of researchers. Grateful for Gorilla’s role in advancing science!"

Social Robotics and Language, Potsdam University

Mixed Methods Research

Quickly create surveys and self-report measures for your experiments.

See more

Build classic and novel reaction-time tasks with ease.

See more

Design your experiment structure intuitively. Launch with confidence.

See more

Gamify your tasks to increase motivation and sustain attention.

See more

Build a realistic experimental shop to study consumer decision-making.

See more

Make your tasks playable by multiple participants to study group behaviour.

See more

Academic Support

Our friendly, qualified support team respond rapidly - usually the same day!

Our onboarding webinar videos provide expert coaching, so you can get building quickly

Sign up free to watch

Troubleshoot your experiment and get your questions answered live

Learn more about office hours

Access a library of webinars and step-by-step documentation

Browse All DocumentationGorilla gives labs, departments and research teams the power to address their research questions at scale

Move your work forward quickly - with tools that make it easy to share your work for review, delegate experiment admin, and create shared libraries of pre-approved resources

Explore new ideas with confidence, knowing your work saves automatically. You can't break it or lose your work. And you can make changes quickly - even after you've lanched your study

Want to add your own code without managing a whole server? Gorilla is a no-code experiment builder, but those who prefer the option can easily add scripts to extend the tools

"Gorilla opens up a wide range of behavioural tasks including randomised trials and reaction time behaviour. It is easy to set up a task for participants to complete at home over the internet, so I can use it to collect useful behavioural data from participants across the UK. I launched a study recently, went to lunch and came back to 400 participant responses."

Senior Lecturer, Anglia Ruskin University

Tools to make good science easy for students, researchers and supervisors

Teachers

"What we've managed to do with Gorilla is give students the tools and templates to make their own experiments, with minimal supervision. Students can go out and test a hypothesis via social media. Results flood in from all over the world, and they're creating this incredible range of studies. It's a much richer learning experience."

Senior Lecturer, UCL

Gorilla is approved by 300+ universities worldwide

Hosted in the EU

Penetration Tested

Two-factor Authentication (2FA)

Conformant with WCAG 2.1 Level AA. VPAT available.

Fully GDPR and BPS (The British Psychological Society) compliant

Easy application to your Internal Review Board (IRB) or Ethics Committee

Shortcut the weeks and months to collect high-quality data. Get on-demand support to build, preview and pre-test your experiment with our free plan.

Choose from dozens of sample tasks to clone and customise for replication. Access free, 5-minute tutorials and a library of bite-size resources.

When you’re satisfied you can measure what you want to measure, choose from academia-friendly pricing tiers, to host and start collecting data.

With group savings - great for labs and departments.