Subscribe to Gorilla Grants

We regularly run grants to help researchers and lecturers get their projects off the ground. Sign up to get notified when new grants become available

Spotlight on...

I study voice identity perception, that is I look at how we recognise familiar voices, how we discriminate between unfamiliar voices and also how we learn new voice identities.

I have run quite a few studies on Gorilla by now. One of the first studies I ran was trying to work out how people form representations of newly learned voice identities. When we hear voices in everyday life, one striking feature of these voices is their within-person variability: the voice of the same person will sound different depending on each conversation partner, speaking situation and speaking environment (e.g. giving a job interview versus talking to a friend versus shouting at the photocopier). Despite this within-person variability, we can recognise familiar voices with reasonable reliability. So, how do we make sense of all of this variable and potentially messy input? There are proposals in the face and voice identity perception literature suggesting that people form representations when learning new identities that are based on abstracting the averages of all experienced instances of that face or voice.

In order to test this prediction, we decided to train listeners to learn to recognise – and thus form a representation of – 3 voice identities. The acoustic properties of the training stimuli were carefully manipulated such that each voice’s training stimuli formed a distribution that was missing its centre. So, in this set up, listeners never heard the average acoustic properties of the voices during training.

At test, we then presented listeners with novel recordings of the 3 trained identities that mapped onto the acoustic properties they had heard during training. Crucially, we also now presented listeners with recordings that fell onto the average of the training distributions. If averages are indeed abstracted during identity learning, we would expect that listeners are as good or even better at recognising the trained identities from these average recordings compared to the other recordings.

And this is exactly what we found: Listeners were more accurate at recognising the recordings that corresponded to the unheard (!) average than the recordings that fell onto the previously heard training distribution. We could also show in a complementary analysis that accuracy in fact increased the closer a recording was to the average in terms of its acoustic properties. We took these findings as an indication that people must have indeed formed a representation based abstracting voice-specific averages as opposed to the trained exemplars.

We are now looking into running follow-up experiments to find out more about the underlying mechanisms that may be underpinning these findings.

“It is amazing how quickly anyone can set up a study from scratch.”

Our article has been published by Nature Communications.

Switching to online testing with Gorilla made a huge difference to me. It saved me time and hassle when setting up experiments and studies. There are also essentially no compatibility issues when switching computers or sharing studies. Additionally, I suddenly had access to participants throughout the year, which had previously been an issue.

By having my study online running in a browser, it now takes me one afternoon to collect my data as opposed to having to test in person for weeks and weeks.

It will be a lot easier to get adequate sample sizes when testing online, which improves the quality of research.

Our studies usually involve playing sounds to people, so we always need to make sure people can actually hear our stimuli. There is a useful screening (Woods, Siegel, Traer & McDermott, 2017) that we use at the start of our studies to make sure that people are wearing headphones and are not listening to our recordings on tinny laptop speakers. Throughout our tasks we also use auditory attention checks to make sure people keep on paying attention. These checks usually take the form of catch trials where instead of playing one of our experimental stimuli, we present a recording that is instructing participants to pick a certain response for this particular trial (e.g. “Please press 7 now”).

It is really easy and intuitive to use Gorilla. It is amazing how quickly anyone can set up a study from scratch. This is not only useful for my own studies but now students can easily create their own tasks for their research projects, which helps to really get to grips with their experiments.

For my undergraduate, I studied linguistics and phonetics, which set me off on the path of doing auditory research. How did I get interested in this somewhat niche field? Well – I watched My Fair Lady when I was a teenager…

Cycling, trying to find the delicious cinnamon buns or almond croissants in town.

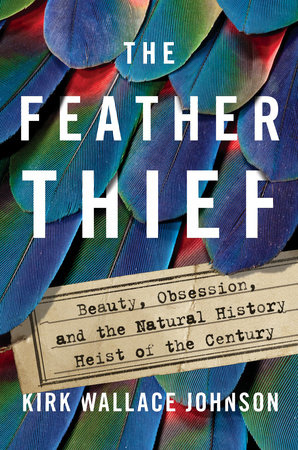

Not necessarily a traditional (pop) science book but The Feather Thief by Kirk Wallace Johnson was an interesting read. I know a lot more about early naturalists, the exotic feather trade and fly tying after reading it!

We regularly run grants to help researchers and lecturers get their projects off the ground. Sign up to get notified when new grants become available