Subscribe to Gorilla Grants

We regularly run grants to help researchers and lecturers get their projects off the ground. Sign up to get notified when new grants become available

In this interview Josh explains how he used games to add a realistic social dimension to his experiments and to make them more engaging for his participants.

Josh has worked for over 15 years in both industry (GlaxoSmithKline, Nielsen) and academia (Trinity College Dublin, ETH Zürich, Royal Holloway University of London) investigating a range of topics including: neuroimaging methods, neuroeconomics and social decision making, rule-based learning and automation, early markers of cognitive decline in ageing, and reward and motivation in autism spectrum conditions. He currently has 47 peer-reviewed publications and has won over £1.5 million in grant funding. He holds a BSc in Psychology and PhD in Cognitive Neuroscience from Royal Holloway University of London.

There is a growing trend for researchers in the field of psychology to use games in their experiments. This interview is part of a series interviewing pioneers the field of gamified research who have used Gorilla to develop their experimental designs.

My research is about social decision-making, but I often worried that terms in social psychology were quite vague and ill-defined. In fact, I’ve written a blog about this in the past (Knowing me, knowing you? Do Psychologists understand each other?), and in my opinion it’s a bigger problem for social compared to cognitive psychology. To get around this I’ve often taken tried-and-tested tasks from value-based decision-making and changed the social reference (i.e., answer the question for yourself or a friend or a stranger). There are lots of fun and realistic gambling games which have a solid mathematical framework underpinning player behaviour, making it very clear what you’re investigating. They’re also incredibly malleable as you can turn them into social tasks through something as simple as getting participants to observe other players or predict someone else’s choices.

One of the things we noticed when doing these projects was that undergraduate students show very little variability. I think it’s the whole WEIRD (White, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic) population problem. We had 100 mostly white, mostly female, psychology students all between 18 and 30 years of age do the task in the lab and we just found so much homogeneity in the response profiles.

What I was really interested in was not just social decision-making but in the individual differences and trying to understand why some people are more influenced by others. So I wanted to move online to get to a wider, more diverse and representative group of people to do my experiments.

Well the idea of using a game was a follow up to the need to go online. One of the things that we’ve noticed with online experiments is that if you’re paying people or recruiting students, that’s fine, but it’s not easy to recruit if you don’t have money or credits to offer students. It’s even harder if you need you need a specialist population that are already exhausted from psychology studies. You need to engage them and motivate them to be part of your experiments. This was where I thought, there is such a clear difference between having a nice animated game that does what we were looking for, versus what I could build, which was just boring coloured boxes which wouldn’t have felt anywhere near as realistic or engaging.

Sometimes you can perform social decision-making experiments with real people and multiplayer games but what I did this time was to trick people into thinking they were interacting with real people. That’s why the realism and framing was so important. When it looks like a slick product, people are more likely to believe that it’s a real person they’re playing with.

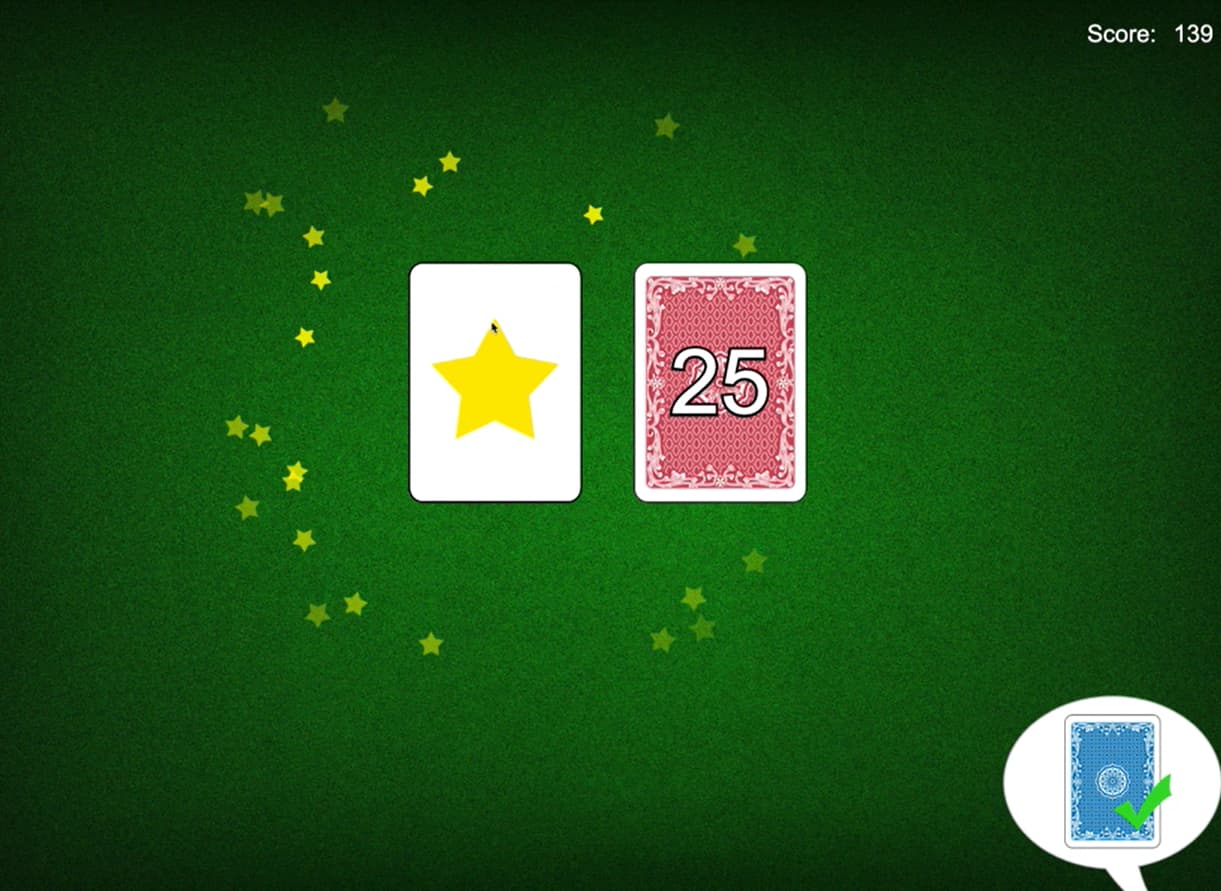

The task itself is quite a fun one. You have two decks of cards, a red deck and a blue deck. One deck is stacked with more “winning” cards than the other and players learn whether the red or blue deck pays out more often. However, each card is also worth a set number of points. This creates four basic conditions:

This creates more realistic decisions that include risk and establish how many more points a player needs in order to take a gamble. This varies a lot from person-to-person depending on how risk-seeking or risk-aversive they are. The game elements are a lot of fun here as you get stars and fireworks when you win vs a harsh buzzer and smoke when you don’t. This made the game much more engaging and enjoyable than the original where you didn’t get any of this kind of stuff.

The social aspect of the game comes in with a little image of a financial advisor and a speech bubble in the bottom right corner that gives you advice about which deck to choose. We varied the quality of the advice and also the risks and rewards associated with the decks, within-subjects. We wanted to see how much emphasis people were putting on the social information they were getting and how much of their decision-making was based on past experiences, as well as how their decision-making was affected by the volatility of the advice and decks of cards. We tend to ignore advice in a stable world, but if the world is constantly changing then we pay more attention to what other people have to say.

There are so many facets to think about. Most gamification works with badges, points, and leaderboards, but what’s really cool are the research games. The one’s where you don’t know you’re doing a task. These tend to be more enjoyable and people will come back more often and recommend it to other people. Although we didn’t have to do it with this experiment, if we wanted to do repeated measures and we wanted people to come back and play the game once a week to see if there’s an improvement, *you need to make it enjoyable and fun if you want people to give up their time. There’s also ecological validity to think about. In our situation, we have a nice deck of cards and it looks a lot like something you’d have from the app store, something that people are engaging with in their daily life. The hope is that performance would be closer to what you’d expect to see in a real-world gambling situation.

In terms of stuff that I wanted that couldn’t be done, I guess the next stage would be participants dealing with real people. Something like The Hive where you actually have real multiplayer, but there wasn’t anything in this experiment that I thought couldn’t be done.

It does depend a little. There are a few situations where I would go back to basic experiments, such as when you need people to be very focused on a specific item and the gamified features might distract them from the task, like if you’re doing eye tracking. You would also need to think about whether gamification actually contaminates your results by changing baseline motivation, or if you are actually changing something in your experimental design. Within all of my experiments, I always try to have within-subject control trials so you’re always comparing against a baseline that is inbuilt into your experiment. So I don’t think that’s such a big problem. In most cases, I definitely would use gamified tasks in the future.

We regularly run grants to help researchers and lecturers get their projects off the ground. Sign up to get notified when new grants become available